It’s undeniable that drugs are becoming part of the mainstream. Our latest content series set about uncovering the most progressive and exciting emerging voices on the topic, sitting down with them to understand their perceptions and opinions of drug culture in Ireland, and the world today.

This is Truth on Drugs. Future thinking on drugs and society.

In April 2022, 40-year-old Laura Heath was sentenced to 20 years in prison for manslaughter. Back in 2017, her seven-year-old son Hakeem Hussain died after having an asthmatic attack and was found alone in the garden of their home in Birmingham. His mother had modified his inhalers, using tinfoil and elastic bands to make them viable for smoking crack cocaine. Heath is one of a large number of people in the UK addicted to powdered cocaine or crack cocaine: the two are almost chemically identical, but the latter is usually mixed with water and sodium bicarbonate to form solid rocks. Between 2020 to 2021, 4,545 people in the UK were in active treatment for crack cocaine addiction while 19,209 people were for powdered cocaine. In Ireland, the number of treatment cases more than tripled from 853 in 2014 to 2,619 in 2020. Cocaine is an illegal stimulant that has been in circulation across the globe for decades — but what exactly is it and where does it come from?

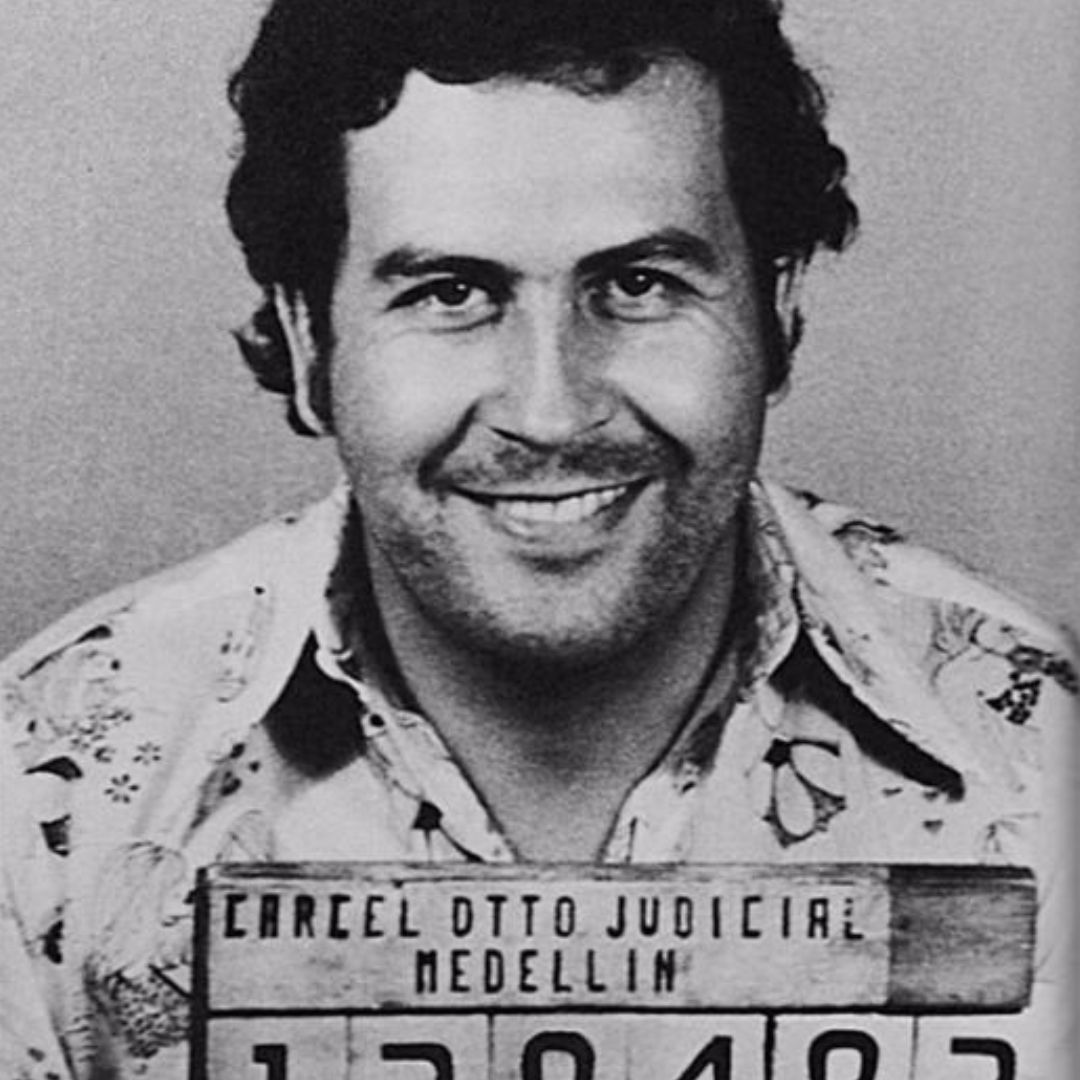

The drug stems from the coca plant, which is native to South America. Farmers strip the plant of its leaves before completing several chemical filtration processes –– which include kerosene and sulphuric acid –– to produce white powdered cocaine. Colombia was and is still the biggest producer of cocaine in the world, and also once housed the most infamous drug cartel to ever exist: the Medellín Cartel. As detailed by popular modern-day TV series like Narcos and Snowfall, cocaine rapidly gained popularity in the 70s, largely thanks to the cartel’s founders. Griselda Blanco, Carlos Lehder and Pablo Escobar set up a system which linked producers, traffickers and distributors together to supply US cities like Los Angeles, Miami and New York with the drug. Between 1972 to 1993, it’s estimated that the cartel turned over around $4 billion a year.

Nowadays, the same framework exists, but more players have a slice of the pie. According to VICE’s The War on Drugs Show, Mexican drug trafficking accrues between $19-29 billion a year.

“The transportation networks have become more extensive,” explains Harry Shapiro, the founder of DrugWise, an online resource that aims to collate scholarly papers, news reports and other information about drugs in one place. Shapiro says that in the UK, Albanian drug gangs liaise directly with cartels to supply the country with the drug. In 2017, ITV ran the two-part documentary, Gordon Ramsay on Cocaine which gave an insight into this system by showing Albanian dealers in action.

“Albanian crime gangs currently dominate the UK cocaine trade because of their willingness to use violence,” Ramsay explains, a detail divulged to him by the UK’s National Crime Agency, tasked with intercepting the gangs’ activity.

At present, Shapiro feels there’s little to no deterrent for gang members to stop. “The percentage of drugs that get caught coming into the country is minute, probably less than 10%,” he says. “There’s so much of it that anyone and everyone who wants it can get hold of it.”

When cocaine first arrived on the scene, it was perceived as an upper-class pastime because of its price tag and the fact that the effects wear off quite quickly, explains Shapiro. However, he states that nowadays cocaine is purer and cheaper, making it a lot more accessible to a wider proportion of the population.

“I actually don’t like it that much but it’s pretty much as accessible as [buying] milk or bread is,” says 23-year-old Evie. Young people seem to be equally into taking illegal drugs as the generations before them. A study published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2020 found that among young adults aged 16 to 24 in England and Wales, powdered cocaine was the third most commonly used drug behind cannabis and nitrous oxide, with 331,000 users admitting to taking the drug that year. The 2019-2020 Irish National Drug Survey found that the average age of first cocaine use was just over 21. Cocaine has held this reputation as a dancefloor drug since the 70s when disco music was in its heyday. Celebrities and other members of New York’s ‘it’ crowd would flock to the infamous Studio 54 nightclub in Manhattan, where cocaine and Quaalude use was commonplace. Last year, Marit Edland-Gryt, who works within the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco and Drugs at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, sought to understand why cocaine is such a popular night-out choice. She published the paper Cocaine Rituals in Club Culture: Intensifying and Controlling Alcohol Intoxication, which uncovered three main explanations: “(a) unity with friends because of shared transgression, (b) the high as a ‘collective effervescence,’ and (c) the possibility to control, extend, and intensify drinking to intoxication”. Stella, a 26-year-old former user, agrees with the last sentiment most: “Not gonna lie, I think cocaine is overpriced as fuck, as I mainly used it as a tool to drink more.”

“Harm reduction does not equate to enabling, it’s about keeping people alive.”

Erin Khar

The effects of combining cocaine and alcohol can be particularly lethal, leading to a toxic chemical substance forming in the body called cocaethylene. Information like this for drug users can be found on the Bristol Drug Project’s website – a registered charity that delivers “confidential advice and support around safer drug use at events” on the basis of harm reduction. This is a system of principles and practices aimed at reducing the negative effects of drug use from a health, social and legal perspective, all while respecting a person’s right to use drugs. Other UK-based initiatives that promote harm reduction include The Loop, which provides free testing of drugs at festivals and events, and Release, which offers free specialist advice on drug use and drug laws to both the public and professionals.

“We need a comprehensive suite of harm reduction measures, well-funded by the government, to help all people who use drugs,” says Release’s Policy Lead Laura Garius. “[There should be] treatment services to specifically recognise the trauma that can result from years of being over-policed and discriminated against for individuals from Black and Brown communities, and to ensure that services are as inclusive as possible.”

Author Erin Khar is a former drug addict and fierce proponent of harm reduction; she penned the book Strung Out: One Last Hit and Other Lies That Nearly Killed Me about her 15-year recovery journey.

“There is a pervasive attitude — especially for those who grew up in the era of ‘tough love’ and the ‘war on drugs’ — that addiction is a moral issue, that it’s as simple as ‘just say no’,” she says emphatically. “What I’d say to those folks is this: harm reduction does not equate to enabling, it’s about keeping people alive.”

Shapiro asserts that there aren’t any clearly defined harm reduction practices in place for cocaine as there are with heroin, for instance, where clean needles are supplied, but he believes that treatment starts with counselling services. By and large, Khar agrees: “If we genuinely want to solve the addiction crisis, we need to offer subsidised long-term aftercare and other social support programs.”

According to ONS, 777 people died of cocaine poisoning in 2020 in England and Wales — an almost 10% increase from 2019 and a five-fold increase since 2012. The National Drug Treatment Reporting System stated in 2020 that the number of cocaine-related deaths in Ireland had increased by 153% since 2010. As it stands, the illicit drugs market across England and Wales is worth an estimated £9.4 billion annually; for perspective, only £600 million is spent per year on drug treatment and prevention. As the cocaine industry expands and governments continue to cut funding, drug deaths and addiction rates look set to rise, making the work of NGOs that advocate for harm reduction all the more important.

“Addiction is not a moral failing,” says Khar. “It’s a public health issue, and people with substance use disorders are human beings struggling with a human condition.”

Essentially, it seems there’s work to be done when it comes to letting go of the long-held stigma attached to drug users — both on a societal and governmental level.

If you or someone you love are struggling with addiction, freephone

HSE Drugs and Alcohol helpline on 1800 459 459.

Follow Lakeisha at @kilokeesh

Truth is the Tenth Man’s Research & Strategy division. We dedicate ourselves to understanding culture; immersing ourselves with the communities and the people we want to win with, to identify the unseen, underlying and unifying insights that we can leverage to enable great brands to grow further.